The ‘Form We All Lie On’: Exploring the Experiences of Mothers Seeking Mental Health Care

The physical part of pregnancy wasn’t bad for me. The biggest struggle was the emotional and mental part.

Mental health conditions are the leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States, and a significant number of these tragic deaths are preventable. Improving mental health screening, diagnosis, and access to treatment early in the motherhood journey can improve outcomes for the entire family.

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Maternal Mental Health Task Force, led by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and the HHS Office of Women’s Health, launched a National Strategy to Improve Maternal Mental Health Care in response to the maternal mental health crisis.

As part of the strategy, the U.S. Digital Service (USDS) conducted a six-week research sprint, incorporating principles of human-centered design, to understand the lived experiences of the maternal mental health journey. This work is summarized in Pillar 5 of the National Strategy. Human-centered design (HCD) is a methodology that places real people at the heart of efforts to improve product or service delivery, by seeking to understand those individuals’ goals, challenges, and experiences.

At USDS, our interdisciplinary teams of product managers, designers, and engineers share a core value of transforming critical services with our users, not for them. To develop policy solutions that truly solve the problems faced by American families, deep empathy and trauma-informed practices are required. Increasingly, human-centered design is becoming a best practice in policy making and service delivery improvement. USDS has also led an interagency team that is integrating a customer experience focus in federal program design and delivery for birth and early childhood.

The USDS team interviewed eleven mothers in nine urban, suburban, and rural states with different racial and ethnic backgrounds. Many mothers had given birth to at least one child during the pandemic. Medicaid covered some, and some were covered by private insurance or health exchange plans, which helped the team understand how different insurance coverage might impact care.

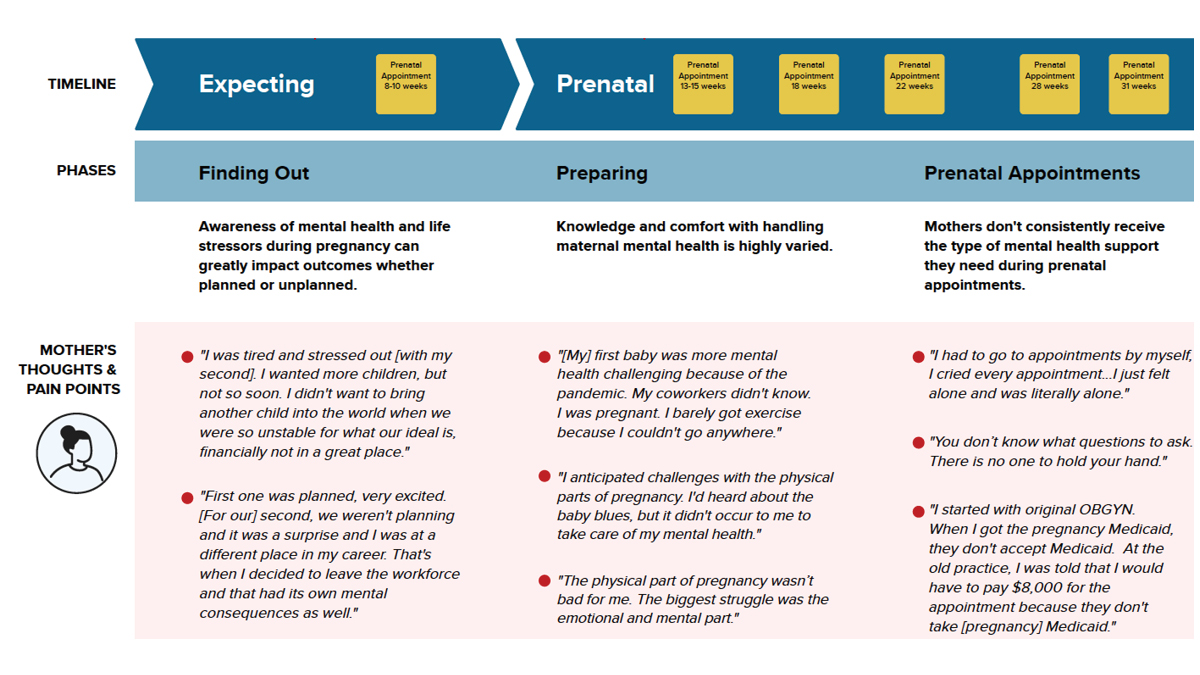

Based on these interviews, the USDS team created a journey map that visualizes the challenges mothers face when determining whether they should seek help, go through screening and diagnosis, and find a provider for treatment.

The Journey from Screening to Diagnosis to Treatment

Data from the visual journey map is described in all parts of the report that is linked. The points that are important are in the article itself. Please see link for the complete data is in the report.

What the team heard

Mental health conditions are hard to recognize on your own

Mothers are often unprepared for the mental health challenges they face during pregnancy and postpartum. While conditions like postpartum depression are more common in the cultural discussion now, other conditions like anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder may be harder for mothers to recognize as valid and treatable.

Many mothers need mental health support from the prenatal period through postpartum, and mental health wellness visits as part of the default standard of care could help catch more early warning signs. Most mothers had just one postpartum visit at six weeks, which focuses primarily on the mother’s physical health after birth. Most mothers are not asked about their mental health during that visit, yet it’s a key opportunity for providers to check in and offer mental health resources and support.

Mothers also shared how they felt forgotten after birth, with all medical attention now turned to their new babies. This can leave them feeling vulnerable and unsupported during their transition into motherhood. As one mother put it, “I felt very cared for all through pregnancy, and then I had the baby, and it was like, okay, you are done, we are done caring for you, and now it’s all about the baby. I was very confused by that dynamic.”

Health, financial, and social stress compound

Pregnancy and postpartum is also a time when a mother’s health and financial stress can compound with the physical challenges of pregnancy and postpartum recovery. This, combined with the lack of sleep accompanying newborn care, creates a perfect storm of risk factors for many women. Mothers also described the anxieties they felt giving birth and trying to stay safe during the COVID-19 pandemic.

One mother told the team, “I don’t have a lot of friends who are parents, and through the pandemic, it was very scary to go in for appointments, ultrasounds, and to see the doctor. My husband wasn’t allowed to go to a single appointment.”

The pressure to be a “good mom” also causes mothers to ignore mental health warning signs because they worry about how they might be perceived for seeking treatment – by family, friends, or health care providers. Breastfeeding, in particular, came up again and again in the interviews. One mother shared, “I consider myself a feminist. I couldn’t let it go that I thought mothers could do it easily. If I were a good mom, I could do it. Why can’t I?”

Mental health screening tools aren’t always effective

Mental health screening tools create anxiety and undermine trust if they are not delivered with care. Many mothers felt there was no context-setting or a conversation about why they were given the screener and what would happen afterward if they scored too high.

The team learned that the screener questions didn’t match how mothers described their experiences. Their responses were influenced by their desires and fears about being perceived as good mothers. The team spoke to mothers of color who expressed a heightened sense of fear due to their perceived pressure to show even more competence as mothers. One woman described the screener as “the form we all lie on.”

Accessing care is challenging

Even when mothers can recognize their own risk or score high on screening, they encounter many obstacles in seeking and receiving care. Finding an affordable provider with whom you can connect, who is available, and who you can access given work and child care responsibilities is challenging. Some mothers attempted to seek care but eventually gave up. Those with Medicaid had an even harder time finding quality providers who accepted their coverage.

Returning to work too soon

Returning to work before they were ready was a major trigger for mental health challenges, particularly in a country where there is no guaranteed paid parental leave. Many of the mothers the team spoke to described their need to return to work meant they had to sideline their recovery and the needs of their growing baby to keep their households financially afloat. As one mother put it, “At four months, your child is not sleeping, you are not sleeping enough, you’re a zombie at work, but still expected to show up in a certain way.”

Opportunities for change

There were also some important bright spots and opportunities to address the needs and pain points the team gathered from their interviews.

When providers–whether a doctor, nurse, midwife, or doula–took the time to ask mothers about their mental health and connected them with resources, they were more likely to be correctly diagnosed and receive appropriate care. Finding more ways to extend care teams through group and peer support models, could help provide much-needed community as they grow into their new role. Doulas and midwives were cited repeatedly as key providers that made a difference in mothers’ experiences. Mothers report higher trust when care teams are diverse and reflect their communities.

Screenings can be conducted as part of an interpersonal conversation, less like an “exam” that you could pass or fail, with more context about the purpose and what comes next. A more conversational approach could help make the screening more effective at identifying risk. A digital screener with more user-friendly language could also be helpful for mothers who aren’t making it to appointments or may feel more comfortable completing it at home rather than in a crowded waiting room where they are also juggling their new baby.

Paid parental leave is necessary for American families to take care of their babies and themselves, both physically and emotionally. Too many mothers are returning to work after just a few weeks when they and their babies are incredibly vulnerable and are still healing. The mental health impact of having to leave your baby and return to work before you are ready cannot be overstated.

Long-term impact

Read more about the six-week research sprint to understand the lived experiences of the maternal health journey conducted by USDS in Pillar 5 of the National Strategy. Priority 5.2 details the importance of implementing recommendations that came directly from the lived experience research.

Based on the lived experience research, the Task Force on Maternal Mental Health included the following recommendations in the National Strategy:

- A national paid family and medical leave policy

- A diverse, interdisciplinary, culturally competent perinatal health workforce

- Peer support and a group care model

- Measures of the quality of patients’ experiences with maternity care, including mental health care

- Holistic care models that integrate treatment of both mothers and babies

- Screenings for different types of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs), such as anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and bipolar disorder

- Human-centered training and implementation of PMAD screening

- Closed-loop referral systems for perinatal mental health

- Continuing education requirements for perinatal mental health providers, including medication management

Pillar 5 in the National Strategy describes just a handful of experiences, but millions of mothers go through similar journeys daily as they expand their families. The mothers the team spoke to bravely shared their personal stories in the hope of helping more families avoid the challenges they faced. Together with HHS’s leadership, our team is proud to have integrated these stories into the National Strategy, and we look forward to continuing to work together – including with mothers – on implementation.

More posts

-

Nov 10, 2022

Nov 10, 2022Meeting veterans where they are with accessible mobile tech

This Veterans Day, we’re honoring our current and former service members by highlighting a collaboration between the Department of Veterans Affairs and the U.S. Digital Service.

-

Aug 15, 2022

Aug 15, 2022A quick guide to inclusive design

Designing for inclusion isn’t just about coding for accessibility or section 508 compliance, it’s about providing equitable and easy-to-use websites and services for diverse populations. Because good design is design that works for everyone.

-

Apr 27, 2022

Apr 27, 2022Tackling the climate crisis with open source

Every one of us has the right to breathe clean air, drink clean water, eat safe, nourishing food, and live free from the threat of climate disasters wrecking our neighborhoods and livelihoods.